Ungrammatical Cinema

It’s not uncommon to hear film being described as a language of some kind. The shot is a basic word; the scene a phrase; and woven together, a syntax. These linguistic analogies prevail because we seek a meaningful translation of the components of film experience. In fact, the idea of visual language has become all but a dead metaphor – now shorthand for the faintest and most disparate notions of style or cinematography.

The thing about such comparisons is that they have an idealized film experience in mind, one where surface plots, underlying narratives and abstract themes all exist as messages. Messages that exist to be represented, signalled and then decoded. If these really were a language, juxtaposing successful communication against incomprehensible noise, then film also has systematic grammar rules. Perhaps, these state that film is equal to communicative force plus compositional mastery.

Enter Tulapop Saenjaroen’s A Room with a Coconut View, an experimental video charging at the seemingly grammatical image and its ability to represent his hometown-cum-tourist resort Bangsaen. “Is there anything else that is not literally in the frame you want to tell me?” its tourist-protagonist Alex asks automated tour guide Kanya, wanting to be let in beyond her hypercorrect presentation. What begins as a well-intentioned search for pictorial truth leads to non-clarity: the seeming self-reflexivity of the visitor who quests for ‘Asia off the beaten track’, never realizing that their expectation of the non-touristy is as equally foreign a construct as the touristy.

This reading seems particularly harsh, but at the same time, one cannot help but share the cynicism of the video’s many explicit declaratives. These are steeped in Saenjareon’s distrust towards not only the touristic reproduction of places, but also the fundamental order behind our ways of seeing. He has even inserted himself in to play Tessa, a second narrator offering nothing but vituperative commentary. He is bent on interrogating the grammar of film – one that has produced hypercorrect images of his hometown, or perhaps any Southeast Asian tourist hotspot – exposing it for having codified and licensed falseness as truth.

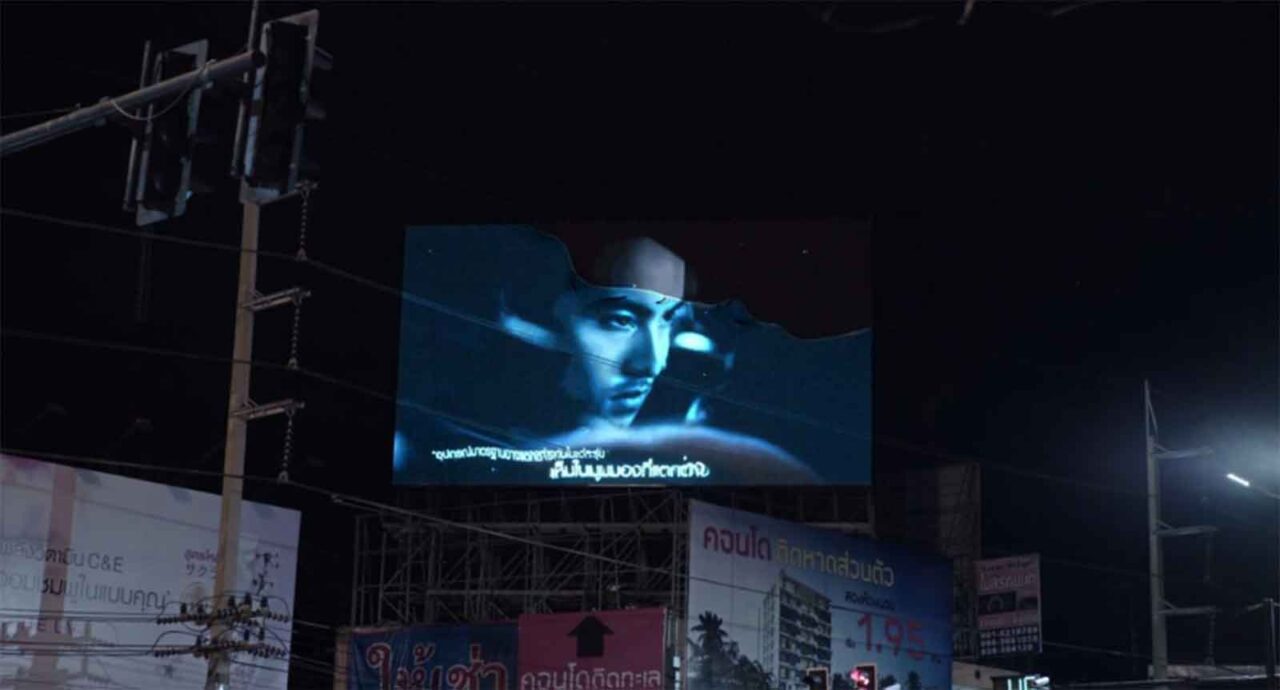

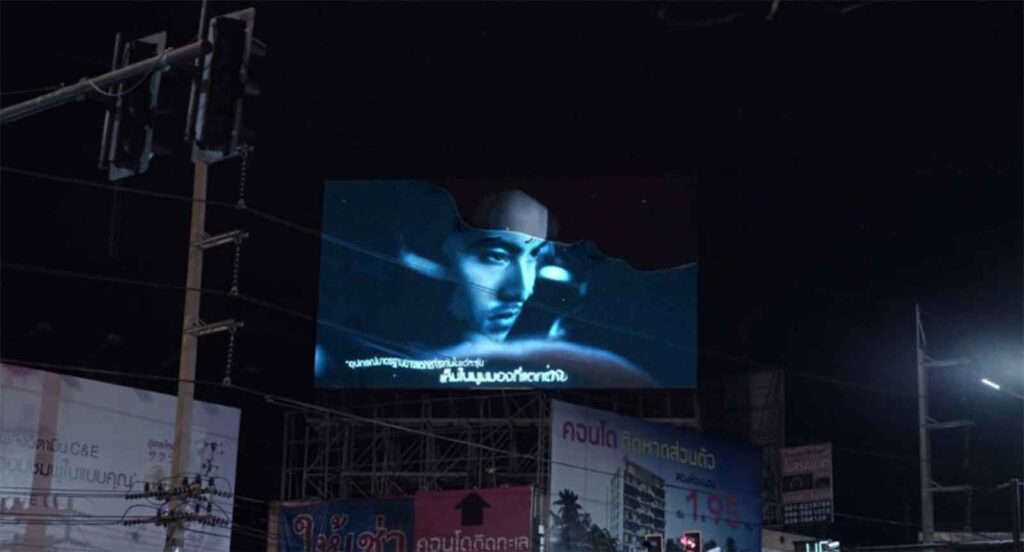

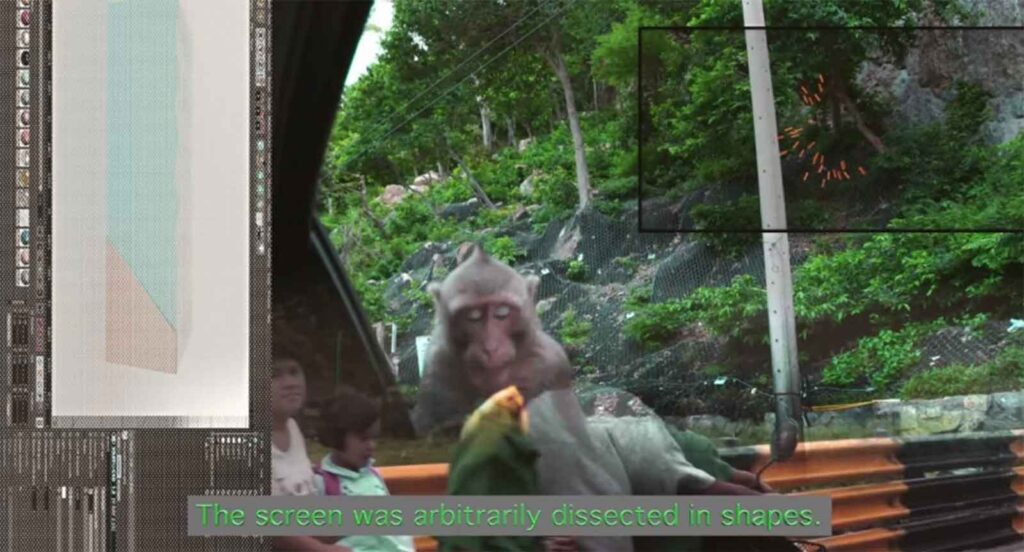

“This is not a sea view. This is a coconut view” is the opening line of A Room with a Coconut View, Alex innocuously remarking about a misleading room description. But more than a tropical riff on the similarly titled novel, these remarks are also the first of the many deceits to come. The Bangsaen we see is disconcertingly still, a simulacra immobilized within the cinematic frame’s four walls. We begin to intimate with the beachside resort’s history as Kanya introduces Kamnan Poh, East Thailand’s political godfather who also developed Bangsaen out of its previous nothingness, a state of paper and graphite. Yet, the images refuse to disclose the full documented truth, having been modulated and tampered with by the cinema, the smartphone and the laptop – all that is left are not documentaries but fictions. Explanations of the past are eclipsed by the GoPro of a waterpark visitor, a thoroughly simulated present. The visitor who comes to find tranquil images instead discovers them in a state of tranquilization.

Saenjaroen’s questioning of images reminds one of René Magritte, whose surrealism interrogated the language translating reality into art and vice versa (true enough, an overt reference is made later on to Ceci n’est pas une pipe).

However, the video’s frames-within-frames specifically conjure two of Magritte’s lesser-known works, both titled The Human Condition. In these works, a canvas covers part of the landscape outside the window, but painted on the canvas is the same thing the landscape depicts – challenging us to differentiate between reality and reproduction, between the frame and the framed. Alas, the landscape, which we realize is painted by Magritte, turns out to be no more real than the canvas is, just like how footage modulated through a cinema, a smartphone and a laptop can only produce someone else’s reality.

A Room with a Coconut View invites us to re-evaluate whether or not these frames truly have a basis in reality – to the extent that film grammar has uncontroversially adopted it as its building block. Do our eyes see the world with the same stillness as Kanya’s overly stabilized output? Or are we better off acknowledging the kinesis and vibration inherent in what we see, the only laws of composition which Kanya’s dream images seem to obey? The coherent frame is no better a representation of reality than its unmodulated, supposedly ungrammatical counterpart.

To escape the frame is to only find yourself in another – this is what it means to never question the frame for its supremacy and sophistry. Vivisecting these compositional rules, Saenjaroen exposes the optics behind what visitors see of Bangsaen. A stencil of a coconut tree imposed on anything, a sea view included, can make it look like a coconut tree. A coconut view is thus principally no different from a sea view.

Film (not just commercial cinema) and tourism share much in common – both are an exercise in narrowing infinite images down into finite durations. Building an artificial film language then becomes an economizing strategy, one that makes narrative comprehensible, reproducible and followable, just like an itinerary. Film grammar aims to reproduce what we see as concrete and unchanging forms, taming its turbulence along the way. Can we perhaps listen to such turbulence and still seek leisure in film images? But no tourist in their right mind wants to feel restless.

“How shapeless we are” the video concludes, its disappointed protagonist unable to work out a compromise between the local and foreign, the touristy and non-touristy, the ordered image and its chaotic referent. Saenjaroen may ultimately remain ambivalent about the touristic state of his hometown, but he has made clear his disillusionment with such rules of composition, their sleights-of-hand, and how they tamper with fundamentally ungrammatical ways of seeing.

We are asked to embrace ungrammaticality, as well as to reckon with the implication that film may not at all be a true language. If I make a recording of human speech played backwards, certainly nobody will make sense of what is being said. On the other hand, a film played in reverse ends up conveying something and it makes meaning without the rules of composition [1]. Should we mark this as an ungrammatical form, or should we recognize that film is programmed with the option to entirely forgo any sense of rule? A Room with a Coconut View convinces me to accept the latter.

A Room with a Coconut View screens on 7 December 2018 (Friday), 9.30pm, as part of Programme 2 of the SGIFF Southeast Asian Short Film Competition. Director Tulapop Saenjaroen will be in attendance

[1] This example was inspired by the work of video artist and film researcher Toh Hun Ping, when he spoke to the Youth Jury and shared his works with us. The work I recall here is Tangibility (2004), where moving image is first degraded, then processed and again in reverse.