Search for your voice, against the trembling wall

By Kathleen Bu

Red Aninsri; Or, Tiptoeing On The Still Trembling Berlin Wall

Thailand / 2020 / 30 min / Thai

Director: Ratchapoom Boonbunchachoke

At SGIFF 2020, Southeast Asian Short Film Competition, Programme 1

In the expected society, every citizen takes on a different role- a specific voice. We are accustomed to take on a certain conventional thinking based on our role in society. The rebels speak up for change, the authorities try to suppress the chaos, and the people in between, the silent majority: follow the crowd. In Red Aninsri; Or Tiptoeing on the Still Trembling Berlin Wall, we are presented with the difficult truth of it all: is some sort of harmony between these groups possible?

The streets of Thailand are dark and silent. We see a figure, wrapped in a trench coat, face covered by sunglasses and a blonde wig. “That girl looks like a spy”, a cat on the street narrates. The figure follows a lady and pulls out a gun, in true detective film form, as we see three flashes of red. This figure, whose face we finally get a glimpse of in the next scene, is Ang, a transgender sex worker leading a double life as a government spy. The ominous voice of the government, represented directly by Ang’s boss, assigns her to investigate Jit, a student activist who is suspected of hiding a Hong Kong-Uyghur activist and has been labelled an “enemy of the nation”. Not given much choice by her boss, who we only hear through an open radio, Ang is forced to dress up as a ‘masculine gay man’ to seduce Jit.

With a written script, Ang practices what to say when first meeting Jit. This is immediately interrupted by the angry ghost of her ex-lover John, who accuses Ang of lying to him saying “Love is probably an accident but trust isn’t. You fooled me. You lied to me. Our love is a lie.” Insecurity and loneliness clearly lie deep within Ang. With jobs that require her to take on different identities, at times a spy, other times a sex worker, the chances of having a genuine relationship with another human being, other than the ghost of her ex-lover, seems low. It then seemed almost expected, yet necessary, that Ang would fall in love with Jit. A forbidden love is always more desirable, but it is also equally fateful, and its outcomes inescapable – a love that forces you to grow in some way. This sort of love is exactly what Ang experiences with Jit.

Following this character arc, the filmmaker cleverly plays with sound design using hilarious dubbed dialogue for all the characters, with an overarching message to, almost literally, find your own voice. Referencing Thai cinema in the Cold War era, it also critiques a past where every actor was dubbed by the voice that suited their roles. “The hero sounds heroic and the villain sounds villainous.” Every character speaks the way we think they would: Ang has a sweet tender voice, Jit is an enemy of the nation and therefore has a nasal, almost pathetic voice, and the voice of Ang’s boss booms and threatens.

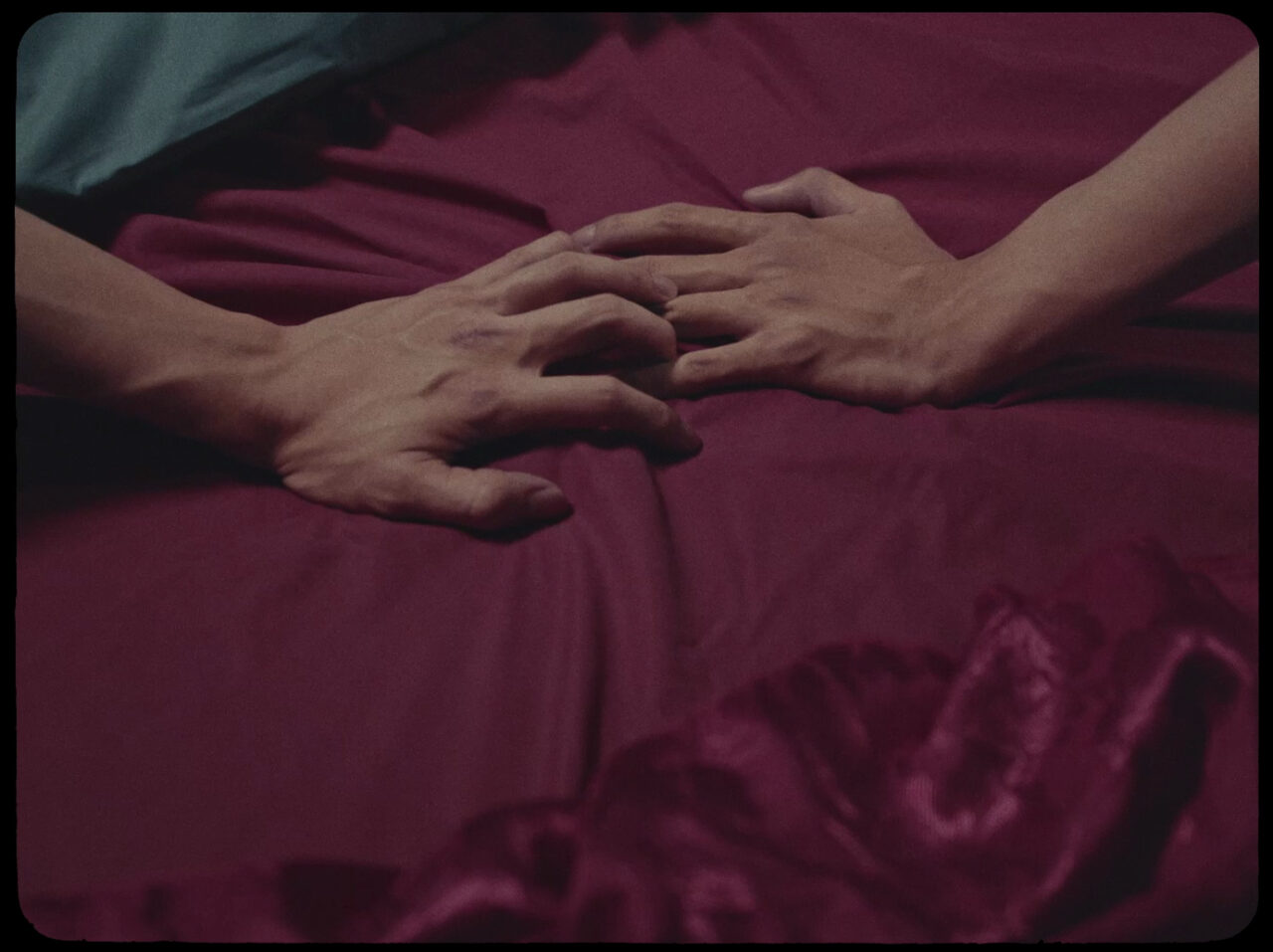

A bulk of the film dwells on scenes where Ang and Jit are alone in the bedroom, simply holding hands or talking to each other. This is also when the behavior of Ang and Jit starts to become more naturalistic, free of highly stylistic blocking or awkward movements. In one of the later bedroom scenes, Ang’s character seems to grow more confident of himself, a step closer to finding her own voice: “I have many things to do in my life than being with someone I don’t like”, she says. Jit looks at Ang trustingly as they take their relationship to the next level of intimacy. Their bodies intertwine as the camera pans to the ominous figure of Ang’s boss, a reminder that the authorities are always watching. After this, Jit reveals to Ang his true voice – the dialogue of Jit turns to a diegetic one as he tells him “This is my voice. I’ve played the bad guy role for a long time. I know it isn’t my own voice. It takes time to stop using other’s voices and use your own. You can do it too Inn. One day, you will no longer use that artificial voice… not this dubbed voice from old films.” The film then is split into two parts, one that is extremely staged in its blocking, camera angles and acting, the other after Ang ‘finds his voice’ and more naturalistic in its stance.

Hidden by the guise of humor, lies a deeper and urgent social criticism: it is one challenge to find our own voices, but another to be smothered by the power of authorities before we can break the Still Trembling Berlin Wall.

There is a moment where Ang lies with Jit in bed and asks him out of the blue, “I’m wondering. You read. You know a lot. You know about the past. But what are you gonna do with this knowledge?” In a moment of self-reflection, I found myself questioning my power in society and whether the responsibility to make change does fall on my shoulders as well.