Keeping Time in Tellurian Drama

By Teo Xiao Ting

Tellurian Drama

Indonesia / 2020 / 26 min / Bahasa Indonesia

Director: Riar Rizaldi

At SGIFF 2020, Southeast Asian Short Film Competition, Programme 3

For moments undocumented by the rigid click of minute hands, we measure the passing of time with our sensorial selves. Time here is fluid, keenly felt in degrees of light and through cycles of germination and decay, though we have since conceded to the mechanical clarity of clocks. What we have lost due to colonisation is more than land—we have also been alienated from our natural world, alongside our ancestral knowledge. A quick Google search tells me that the “universal day” takes its cue from the local mean solar time in England, and has been that way since 1847.

Tellurian Drama, a docufiction short film directed by Riar Rizaldi, weaves together our present perception and measurement of time, and the power that natural structures such as mountains hold. More than an examination however, it also provokes the desire for truths buried by official narratives, in a way that less uncovers “invisible histories” than it complicates our current obsessive drive towards decoloniality. Opening the film is an illustration of the Indonesian archipelago, as a voice-over in Bahasa Indonesia traces its genesis: a particular Krakatoa eruption split the land up into fragments unreachable to each other. The central subject is Radio Malabar, a project initiated by the Dutch in 1923, said to be the first radio station to facilitate intercontinental and wireless communication in order to escape British surveillance.

In the film, as is in reality, actual documentation of the radio station’s history is sparse at best. Where there are gaps in history, Rizaldi intercedes with a certain fictional Drs. Munarwan, a pseudo-anthropologist whose research surrounding Radio Malabar is what Tellurian Drama draws upon. Through excerpts of his research presented through intertitles, we learn of his investigations and ruminations of the subject. According to Drs. Munarwan, the mountain and land Radio Malabar sits on are not static deposits of rocks, but active agents, with vast potential energies that have fueled the entire project. According to Drs. Munarwan, the radio station is not just a project of media technology, but also of geoengineering. According to Drs. Munarwan, who disappeared mysteriously in 1986, and whose papers serve as entry points for subsequent researchers, there are bits of “truths” that we can only access through the descendants of those who have lived through the past. Most information can only be gleaned through deductions or speculations, and the only reliable sources left are inherited memories of those who have descended from the indigineous peoples, who were forced into labour to build Radio Malabar.

More than playfully introducing a fictional researcher with fictional academic sources, Tellurian Drama also stitches together archival (and scripted?) interview footages, splicing them with on-the-ground documentation of the forested ground upon which the ruins of Radio Malabar now stand.

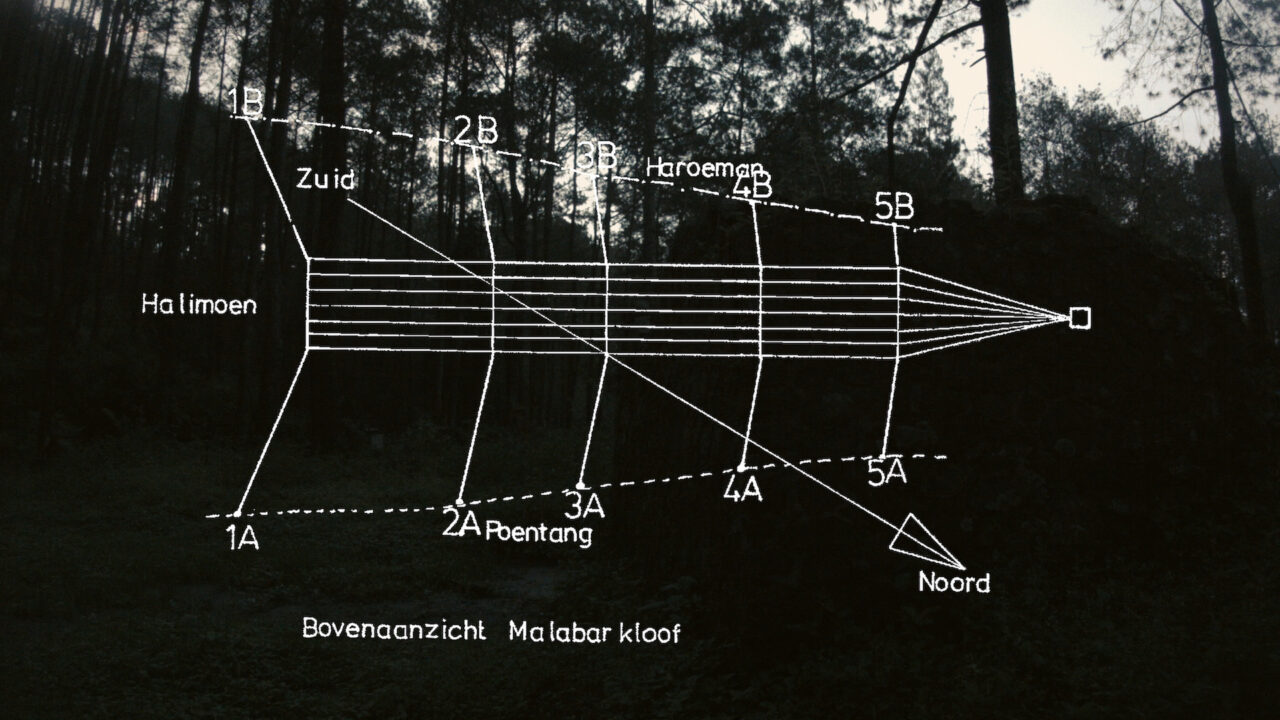

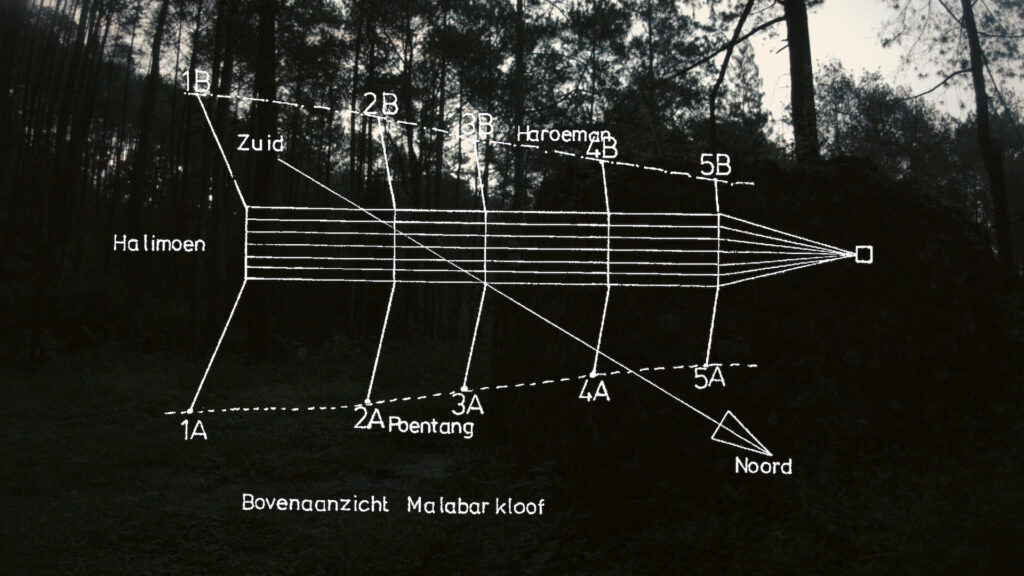

My primary access to the film is through English subtitles; despite Singapore’s national language being Malay, my knowledge of it and its related languages is cursory at best. A remnant of Singapore having been colonised by the British, though that is a gross simplification. As Tellurian Drama introduces intricate diagrams after diagrams of its subject, Radio Malabar, my eyes flit between trying to take in the information that it is trying to share with me, and the subtitles that richly dissect the radio station’s significance and historical imaginations. An uncanny sense of playing catch up, also a sentiment alluded to in the film. As a docufiction piece, we are invited to join the film on a speculative journey to piece together what the radio station actually is alongside the narrator.

Any and all bits of information are crucial in this attempt to understand what exactly Rizaldi is trying to explore, which makes the mediation of English subtitles meaningfully frustrating. What is lost in translation in Rizaldi’s (re)construction of Radio Malabar? As an English speaker, what parts of this narrative am I not meant to access? At this point I entertain the thought that perhaps Tellurian Drama is also an elegy, an offering to the histories we sidestepped due to the ease that an “official narrative” provides. Especially so when the film ends with a proposition against the government’s intention to reframe Radio Malabar as a tourist attraction, to capitalise on its mystery as a historical site.

In navigating colonial remnants, Rizaldi sharply expands the project of decolonisation beyond reclamation or acknowledgment. And in Tellurian Drama, it seems futile to reclaim a previous history, or to belabour the remnants’ historical significance, when there is a more utilitarian alternative at hand: to view colonial remnants as raw materials to serve existing or future needs. At the same time, the film asserts the mountain as the main energy source for the activities that it hosts, rather than a passive container for the lives and time that pass through it.

But however provocative the film’s own decolonial project may be, its conclusion deflates and dismantles whatever it so meticulously set up. As we are shown blueprints after maps, for the transmutation of Radio Malabar into a geoengineering project, the closing sequences show a lone stray dog in the middle of the field looking on, while workers clear the site of debris in preparation of its reopening as a tourist attraction. The scene cuts to a lone man plucking the strings of a siter in the middle of the forest, dressed with a black velvet peci and black sarong, before he pierces the meditative twang with the sound of the flute. He mourns on behalf of the mountain, whose vast energies will not be acknowledged and instead will be seen as just a piece of inert land upon which Radio Malabar sits on. I am not privy to the exact specifics of his grief; there are no English subtitles for his song.

As the camera pans out, we see that he is sitting atop a broken tree trunk, precarious yet certain in his trembling voice. While the film fades to black, his voice continues reverberating, carrying a song I do not understand, am not meant to understand.