“If the government says it’s a hoax, then it’s a hoax!”

By Charles Kurniawan

That is what Indonesia’s Communication and Information Minister Johnny G. Plate said during an interview about Indonesia’s controversial new jobs creation law. The law has been controversial since it was proposed. Influencers are hired to promote the law, a law that has been claimed to favour foreign investors more than workers. The government was also in a rush to pass the bill, passing at midnight a version that was not even final. Demonstrations were held to protest against the law in the middle of Covid-19 pandemic, while the government did little to explain the law. Some ministers just said that people should read the whole script to understand, even though the law runs roughly for a thousand pages.

It is not easy to criticize the authority and their regulation and to be heard. Sometimes it is hard to discuss political issues while seeking factual information. Filmmakers use films to discuss political issues and express their take on the issue. And at the 31st Singapore International Film Festival, there were some interesting and stylized short films about expressing one’s personal voice as a citizen.

Red Aninsri; Or, Tiptoeing on the Still Trembling Berlin Wall tells the story of a ladyboy spy, Ang, on an undercover mission as a masculine gay man to lure student activist, Jit. This short is very conceptual. The director, Ratchapoom Boonbunchachoke dubs the actors’ voices, referencing the conventions of Thai cinema during the Cold War. The dub each actor and actress receives also happens to be determined by their role: hero or villain. The authority gets to decide such roles, even though their presence is only through a dubbed voice. It resembles an espionage film: missions come in from a voice through a radio.

Jit gets a villainous voice. With such a villainous voice, the authority sets a narrative for people to believe. Voice here also can be a metaphor for citizens’ aspiration. The characters’ voice gets dubbed and they cannot use their real voice from the start. Even when they can use their real voice, the authority still decides for them what is right and what is wrong. It is very interesting to see how Boonbunchachoke utilizes something from the past to discuss the present.

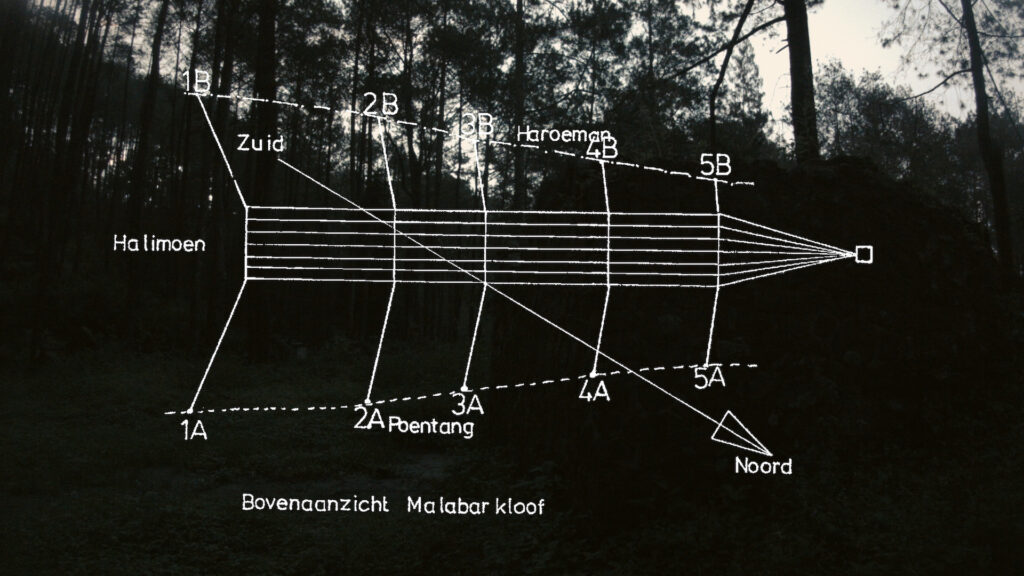

Indonesian artist Riar Rizaldi also uses film and video as his mode of engaging political situations. In Tellurian Drama, Rizaldi seems to dive deep into the realm of conspiracy theory. This docufiction combines the footages with distorted texts from the book by a pseudo-anthropologist, Drs. Munarwan, as well as the blueprints of Southeast Asia’s first radiotelegraphy station, Radio Malabar. Facts and fictions are blurred such that they are no longer differentiable. It portrays the current political situation in Indonesia where the people are fed with some information, information often fabricated to fit into the narrative of the ones who also set the agenda.

The visuals of Tellurian Drama are reminiscent of Romantic art, where nature is greater than humans. Rizaldi offers the alternate reality of Indonesia if the state had utilized its natural resources for the benefit of the people. This idea of alternate reality is repeated by the narrator for several times, yet the authority is planning to transform it into a historical site and tourist attraction. Indonesia is a big country with a lot of natural resources. This film feels like Rizaldi’s subtle way of expressing his disappointment at the authorities’ decision. Imagine back then people in the colonial era could do so much with Radio Malabar, what the authority could have done with more advanced technology in this era. This film resonates our expectation towards the authority’s decision: disappointed but not surprised.

Horror films dominated the Indonesian film industry during the New Order era (1966-1998). Films had to receive approval before going into production. The authority controlled what kind of films people watched during this era. In a separate video essay, Ghost Like Us, Riar Rizaldi explains the conventions of horror films in the New Order era, as well as their relationship to authority. These films were full of violence and sex, but only for these evils to be conquered by good. Part story and part morals, the conflicts in such films were always resolved by the military, religious institutions and the authorities, in epic battles at the end. The same pattern was repeated throughout the era.

Some of the filmmakers then did attempt to be critical through making horror films. They could not criticize the authority, so they used horror films for their own self-indulgence by showing good will always conquers the devil. Unfortunately, this logic made horror films formulaic, still following the convention.

Growing up in a small town near Bandung, Rizaldi could not relate to the characters of the films from the New Order era. People in rural areas were not getting attention. They are portrayed as pathetic. The film characters and stories were centralized in a big city. The non-existent representation in the films made Rizaldi to think about his identity as Indonesian.