Tracing the Origin of Fear

P.S: The discussion below contains spoilers!

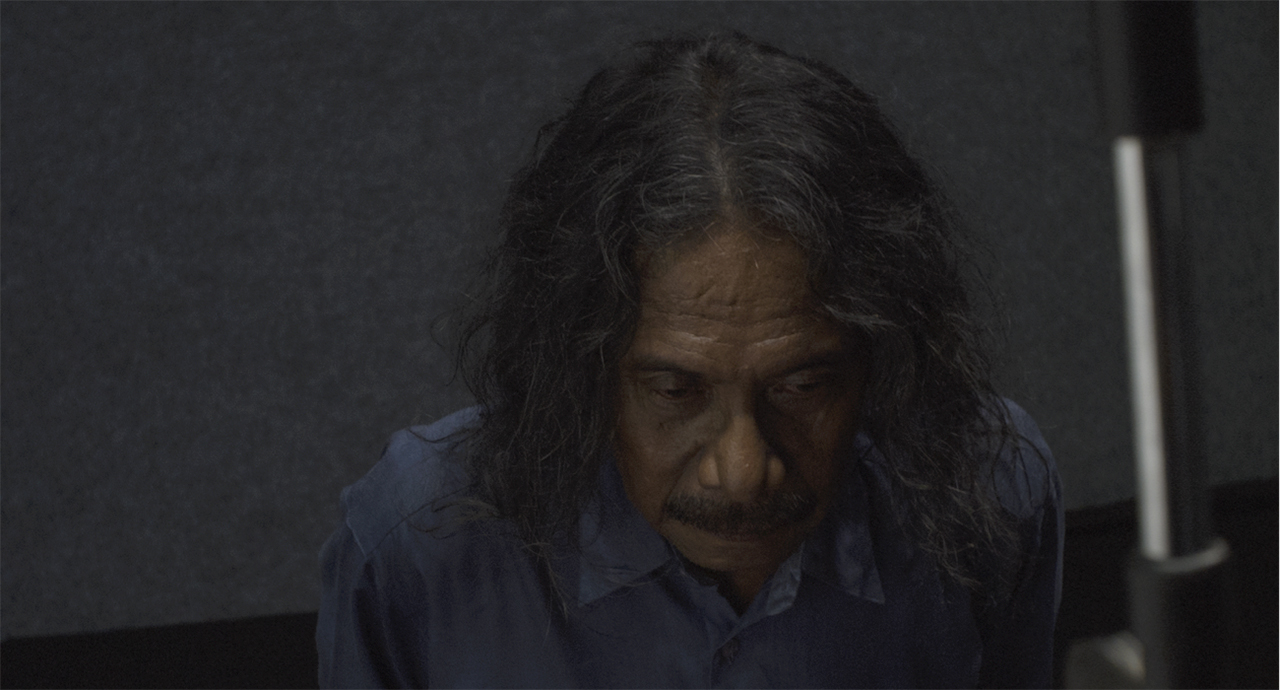

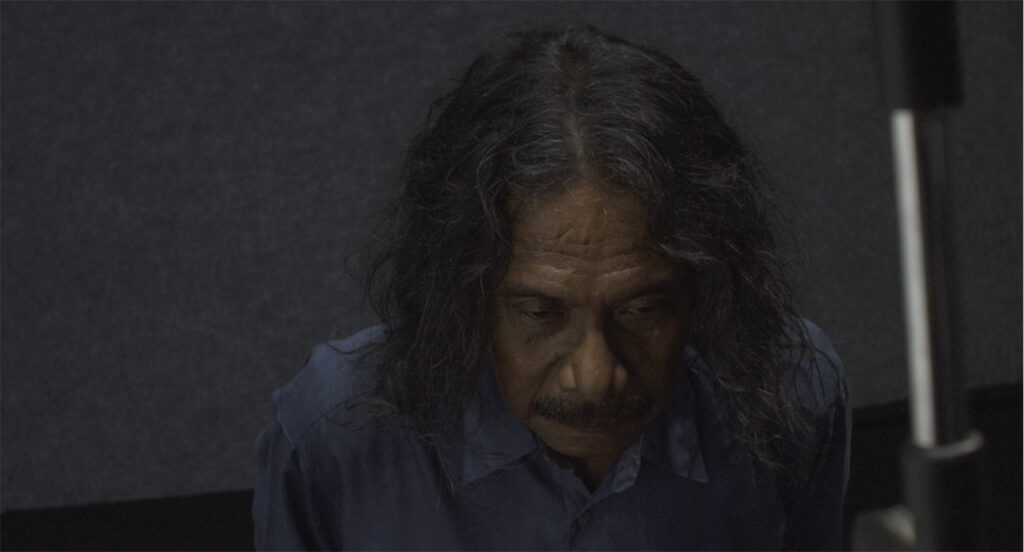

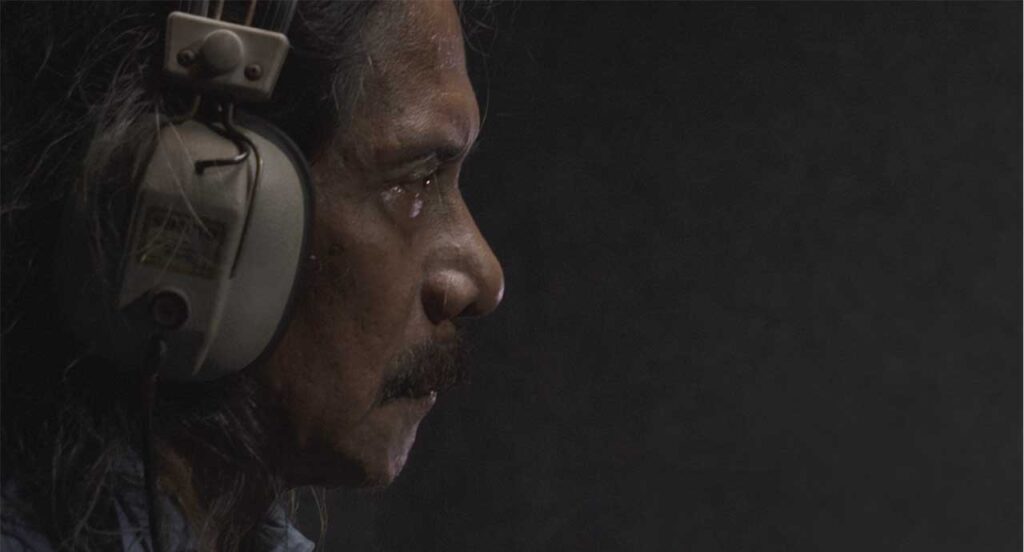

Bayu Prihantoro Filemon’s On the Origin of Fear is a brave and confident debut directorial effort from someone who’s worked primarily as a cinematographer. In its tidy twelve minute runtime, the film smartly and dexterously condenses an irreductible amount of important history into a studio voice recording session for a film of the history it represents. All of this is carried on the back of the film’s committed lead, Pritt Timothy, who plays both the communist leader as well as the Army General in charge of the torture. Owing to its unique approach to storytelling, the film is enigmatic and elusive upon the first watch, grimly comedic and also intriguingly suspenseful. With the text at the conclusion, the film is unlocked, revealing a vast secret history that gives the film an added dimension and charge.

What you are about to read is the transcript of an online conversation between two individuals regarding Bayu Prihantoro Filemon’s short film, On the Origin of Fear. Working primarily as a cinematographer, this short film is his directorial debut. Part of this year’s Youth Jury and Critics Programme, both individuals (Zhi Hao, Yale-NUS and Christine Seow, Wee Kim Wee School of Communication and Information) are two distinct participants, offering differing insights into the film. Their conversation is as follows.

Christine: Let me start by asking you what you thought of On the Origin of Fear?

Zhi Hao: I loved it! I think it was a refreshing use of the short film medium and managed to pack in so much subtext into a very short run time. What’s especially great about it is the fact that the film was not bogged down by the history it was trying to expose and did not sacrifice narrative intrigue for its larger purpose. I also loved how layered the performance of the lead actor was and how he managed to convey both, the fear and the darkly comedic elements of the film whilst working with so little.

C: Yes, I totally agree with you. The performance was brilliant and I felt that the plot was so cleverly thought out that I was thoroughly engaged in every moment! Aside from the powerful performance, what I found really interesting was the fact that the voice actor was playing both the roles of the victim and the aggressor. I felt like the dual-role of the voice actor actually raises the question of the origin of fear?

Naturally, I would think that the fear is felt by the prisoner (the Army General), as the aggressor (Sergeant Heru), pushes him to sign a letter admitting his involvement in the coup movement against the government. However, thinking a little deeper, isn’t the only reason why Sergeant Heru is interrogating the General, because he is afraid of what he might be able to do in the first place?

Thus the film title, On the Origin of Fear. Where do you think fear originates from? From the victim or the aggressor?

ZH: I don’t think there is an easy way to cleanly dissect where fear first comes from, I think that fear is something that once exposed, is highly contagious and catches on extremely quickly. If I had to hazard a guess, I suspect that could have been a reason why the victim and aggressor are both played by the same actor. It might be an oversimplification but I definitely think that the victim-aggressor dynamic is a symbiotic one, with fear as their currency.

The former wouldn’t be the former if not for the existence of fear, and the latter would not victimize if not for the fear of what they are oppressing might be capable of. And that’s just viewing the relationship in a vacuum; if we broaden or place the victim-aggressor relationship on a political scale, like the film has done, then the whole question of the function of fear takes on a different tenor. Fear becomes at once the rebuff for the masses to either cower in fear of the power-wielding aggressors or the galvanizing force that rallies them behind the victims.

C: The film title was cleverly picked as it was thought-provoking, allowing me to truly question the roots of fear. Interestingly enough, the film opens with a top-down shot of the studio, showing a perfect circle. To me, this seems to suggest that the origin of fear is like an endless loop between both the victim and the aggressor.

ZH: I do think so! I think the opening shot crystallizes the relationship wonderfully, where fear begets more fear and the buck gets continually passed along. It is also a rather grim perspective to take, seeing as how the shot of a perfectly formed ring suggests no way out of this predicament. Much like circling vultures or albatrosses, it all seems rather fatalistic.

C: The context of this film is a scripted anti-communist campaign recording, used for propaganda purposes. It’s really fascinating to note how the context of films changes over time, as films have different meanings in different contexts, and in different time periods. It seems to me that governments usually put out propaganda content when they are afraid of what the people might or might not do.

ZH: The idea of the propaganda film fascinates me greatly. For one, I think what lies at the core of the idea of propaganda films is the presupposition that films, fictional or documentary, can have the ability to hold some sort of solid and immutable truth about events or the world, which I think is rather problematic.

What I refer to here as truth isn’t so much the lived or emotional truth that I think films are supremely capable of evoking, but rather the capital-T Truth or facts of reality that are divorced from any perspective or subjectivity. Whether or not ‘Truth’ is even a reasonable concept worth pursuing in art is a different conversation altogether but what I want to hone in on here is the cultural weight of the idea of propaganda. Propaganda, at least to me, conjures up a very specific image of repressive or totalitarian governments, your North Koreans of the world, deliberately disseminating very specific messages and ideas that is often misleading to their populace.

The grand irony that’s not lost on me is that this very loaded notion of propaganda that I hold is also a result of the media and ideas that I consume, which lo and behold, are also a form of propaganda (even if we think they’re the ‘right’ or ‘good’ perspective). A look at the cinema during World War II will reveal as much, for every Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will, we have Frank Capra’s Why We Fight. It’s really just different sides of the same coin.

The film that best expresses this sentiment for me is found, oddly enough in Quentin Tarantino’s Inglourious Basterds (Spoilers ahead but it has been 7 years since the film so please watch it already). If you recall the climax of the film, Brad Pitt’s team of provocateurs infiltrate the movie palace where members of the Nazi party and German public are watching a piece of propagandist cinema. What Tarantino does very intelligently there is to implicate and co-opt the audience (us) into an act of hypocrisy that we are indicting the German audience in the film for. The elation and thrill that we feel when Hitler is shot to ribbons by Brad Pitt is simply a twisted mirror of the mirth that the German audience feels whilst watching Daniel Bruhl’s character in the film (within the film) shoot down opposing soldiers. It’s a sly piece of cross cutting that works to great effect I think, to remind us to keep our own perspectives in check.

C: Haha I sense a Tarantino fanboy here! And although the film was a recording for a propaganda piece, it showed a fair representation of both the Sergeant and the Army General. The film does not give a full view of both the communists as well as the generals that are being tortured. This seems to be a smart inversion, taking away the voice of the communist leaders being discredited, while giving us a glimpse of the torture that the generals must have felt.

ZH: I suspect this might be the director’s attempt at addressing the issue of inevitable propaganda that we’ve discussed above. By giving both the Sergeant and the Army General an equal platform where they both have their voices heard but not so much that either is able to dominate, what happens is that not only does the film not commit the sin it is trying to criticize, it also manages to reflect the solution to propaganda.

What I mean is that by leaving the film open ended, with the clash of both voices equal, the audience is challenged to process both pieces of half information in order to come up with a full view of their own. So in this manner, the film invites and engages us to critically review and consider, which I think is the silver bullet to combat propaganda, which preys on passive and uncritical acceptance.

C: Although both sides were equally portrayed, I felt that there was another master-slave relationship highlighted in the film. And that would be the relationship of the voice actor with the director! The director was never once shown, we only hear his voice without seeing who he is. Yet, the voice actor obediently followed his instructions throughout the film without once questioning him. The director here, seems to be the aggressor, repeatedly demanding the voice actor to put in more emotions, until the point that the voice actor seems to actually be in physical pain!

Somehow, this reminds me of the Milgram experiment, where psychologist Stanley Milgram measured the willingness of participants in obeying an authoritative figure who instructed them to perform acts conflicting with their personal conscience.

ZH: That’s an excellent observation! I do think this interpretation has some purchase if we consider the film as a critique of propaganda on another dimension, that is propaganda from that passes from the power-holders to their henchmen.

I think the film echoes what Hannah Arendt referred to in Banality of Evil, where she concluded that evil or evil-doing comes not from a place of profound perversity or ill, but rather from a place of bureaucracy and unquestioning acceptance of instructions. Viewed in this light, I think we can expand the interpretation of the film to not only as a piece critiquing propaganda but instead more expansively put, as a censure against passive and unhesitating acceptance and obedience, under which propaganda can be subsumed under.

C: Keeping in mind what you’ve said, this perspective really helps to give us a deeper insight into this multi-layered film. It’s also interesting to note how the film highlights the fact that fear was used to propagate fear itself.

I know this might not sit well with all audience members, as we have already seen through conversations with other members of the Youth Jury and Critics Programme, but what do you personally think of the appropriateness of the use of texts at the end of the film? While I do understand that others might have felt that the text was intrusive and perhaps even too explicitly told, it did help to give me the context of the film and without it I’m not sure it would have evoked the same emotions that it did for me.

ZH: I think it is important to consider the weight of the information conveyed by the text at the end of the film before launching to any criticisms of its stylistic clumsiness. I don’t doubt that there are better ways to express the information organically through and within the narrative itself, over having blunt exposition.

That said however, I do think that the grave imperative behind the history of the words does deserve our full attention, reckoning and confrontation; unhidden and undiluted. I daresay to weave the history into the main narrative of the film is to dilute and elide over the heavy history that lies behind those words. Moreover, I think the film has done an impressive job stuffing to the gills within its lean twelve minute runtime, presenting a great deal of very dense ideas and subtexts, and that’s something to be applauded heartily.

C: To cap off our discussion, which I hope you’ve found stimulating, let us give tribute to the film’s laconicity by summing up On the Origin of Fear in one sentence.

ZH: On the Origin of Fear, questions, challenges and considers the origin of all received information and never imbibes anything ignorantly (which I’m just realizing ironically applies especially to absolute maxims like these especially).

C: On the Origin of Fear is an immensely captivating film that draws you in immediately with its spectacular performance, leaving you thirsty for more.

Catch Bayu Prihantoro Filemon’s On the Origin of Fear in Programme 1 of the Southeast Asian Short Film Competition on 2nd December (Friday), 7:00pm, at the National Gallery Auditorium. BUY TICKETS