The Weight of a Place

Locating ‘500,000 Years’, featuring insights from the director himself, Chai Siris

When it comes to films from Southeast Asia, a question that is often asked is, “what makes a film local?” Does it have something to do with the characters and their stories? Or is the ‘local’ related to the filmmaker’s nationality and sense of belonging? One could make a convincing case for either of these questions, but I approach the concept of ‘local’ here by drawing on its etymological cousin, ‘location’. Both words come from the Latin root locus, meaning “place, spot, locality”.

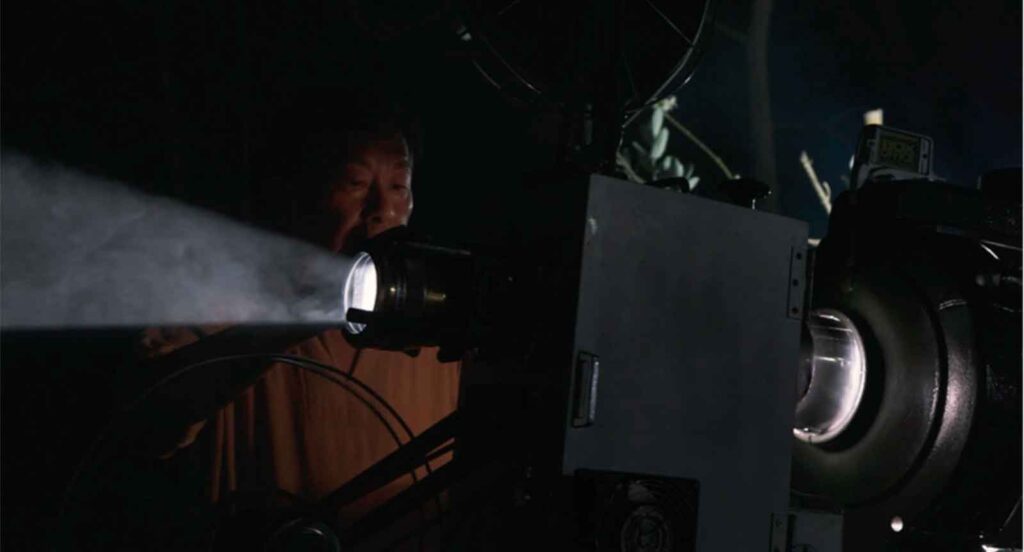

Location in film is like a tomb with a very heavy lid. It’s a difficult task to ask yourself what it means for the film to be shot where it is, and for the film to be shown where it is. But the more you do it, the more you widen that wedge between the tomb and its lid – using strength to reveal the complex intertwining of history and culture underneath. Entirely shot at the site of a shrine to a Homo erectus fossil found in Lampang, Thailand, believed to be 500,000 years old; in the film, we follow an outdoor cinema truck into the depths of a forest to watch the laborious process of screening a horror film on celluloid as an offering to the spirits inhabiting this location.

The first time I watched this film, amidst a series of questions I scribbled down “makes me want to research more”, in that I wanted to read more about the film and this shrine – which I clumsily labelled “man statue”. Instead, I got the opportunity to ask Siris my questions. Now, the more I think about it, the more I realize that perhaps Siris intentionally creates this impulse to question by showing the significance of the location without really explaining why it’s significant.

Instead, he generates an increasing sense of discomfort by playing with the sounds of the forest and the sounds of the old horror film screened for the shrine. About this, Siris explained to me that he sent the sound from the actual footage at Lampang to a Japanese sound designer, Koichi Shimizu, who transformed the “documentary”-like sounds of the site into something more surreal. As a viewer, this created the kind of discomfort I feel when I am in a place I know is above and beyond me. It’s a powerful discomfort. After all, the otherworldly nature of any shrine can only be understood in feelings, not in words.

Even though when I first watched the film, the location’s significance was not immediately obvious, this feeling Siris generates shows that location never comes in a vacuum. There is a poetic beauty in gradually discovering the location and its importance, because after all, don’t most places we find significant in our lives start out as just a place?

A film’s location can speak volumes about how histories and cultures exist and intersect, even if the film itself has no dialogue or narrative. Interestingly, Siris pointed out how this place intrigued him because of the way the Thai people have transformed an archeological site into an animist temple – even dressing the Homo erectus sculpture as though he were their forefather. This response to an archaeological discovery with Buddhist prayers and offerings of a bizarre horror film from the 90s is an odd scramble of science, religion, and kitschy visuals that would be very hard to find anywhere outside of this region. Yet in Lampang it goes unquestioned.

Just as the villagers imbue this site with spiritual beliefs and lay upon it the offering of an outdoor screening, perhaps Siris’ film is an offering to the spirit of a cinema culture at the risk of being forgotten. Capturing the tangible celluloid process of the cinema truck on digital video format, in a meta-narrative sort of way, Siris’ work becomes a film about film cultures and how in their death, they give rise to new ones. The celluloid travels from Bangkok to a shrine in Lampang, but the video goes from there to film festivals around the world.

If the location of a film is the place where cultural production occurs, then the darkened environment of the cinema is the place facilitating cultural consumption. In fact, Siris told me that 500,000 Years was supposed to be a video installation for an art biennale in South Africa. However, for technical reasons that did not work out, and instead ended up being submitted as a short film to the Venice Film Festival earlier this year.

Galleries, museums, and festivals are ritualistic sites of worship in their own right. We seek the space given to us by these organizations to watch and worship the work of artists and filmmakers we believe in. At the same time, the locations of a gallery, museum, or film festival, are platforms for a very specific kind of visual culture. You wouldn’t find any of the Southeast Asian short films in a multiplex, for instance.

Yet even in this seemingly utopic world of visual culture there are frustrating divisions. When I asked Siris about whether he considers 500,000 Years to be an artwork or a film, he said, “I don’t want to answer this question. This piece is art or film, it’s better to keep it open this way because I love seeing the blurred lines.”

This is precisely why 500,000 Years stands out to me. The fact that it can find a comfortable home within the realm of art and the realm of film is telling of the potential short films have to make cracks in the walls separating art from film. And in cracking these walls, it can perhaps change the way we understand what to expect from going to an art biennale or going to a film festival.

It’s the sensitivity the director has in his representation of the shrine that shows how every space we inhabit is a product of a long cultural history. And how we inhabit and represent these spaces will shape their cultural future. In an accidental sort of way, Siris reveals that the locations where we access cultural products, such as a film festival or an art gallery, are also involved in shaping the trajectory of art and film cultures.

The weight of a place is infinitely more than the sum of its parts. As Siris says, this work is simply an observation of what’s happening in Thailand. But thinking about the observation of this location opens the possibility to address histories and futures simultaneously. In the age of the digital, the little shrine in Lampang can travel from Thailand to Venice to Singapore, from gallery to cinema, and perhaps find a safe home in the minds of its audiences along the way.

So, what makes a film local?

The next time you’re watching one, ask yourself: where was this film shot? where was I when I saw it? The answers to these questions will reveal a lot more than you expect.