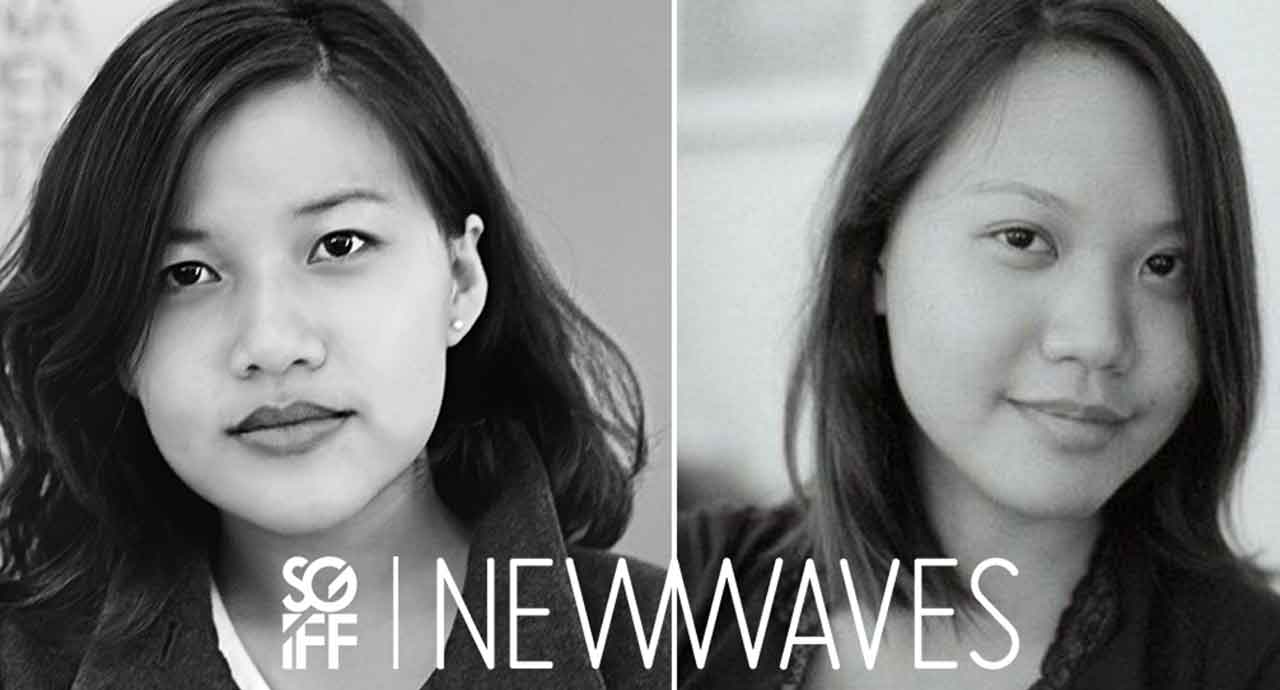

New Waves #3: A Place In Displacement with Tan Jingliang and Adrianna Tan

The third New Waves session which took place on 29 June featured two women—filmmaker Tan Jingliang and entrepreneur Adrianna Tan. Titled ‘A Place in Displacement’, the session explored ideas of ‘home; (as both a physical and psychological space), wanderlust, and a restless desire to explore—all of which Jingliang and Adrianna are no strangers to.

Both Jingliang and Adrianna have travelled (and continue to travel) extensively for work and personal pursuits.

While you might call her a social entrepreneur, Adrianna would be more comfortable to be ‘labeled’ as a ‘kaypoh dabbler’. In India, she runs the Gyanada Foundation, a non-profit organisation which provides scholarships to local girls to help them stay in school. In Indonesia, she is kept busy with her start-up, Wobe, which seeks to empower local women through entrepreneurialism. Adrianna also shared with us her eye-opening experience when she backpacked through and stayed with a host family in the ‘Yemeni warzone’.

Likewise, Jingliang frequently finds herself out of Singapore, as she trots around Asia shooting her short films. She spontaneously shot Sri Lanka Diaries (2013) in well, Sri Lanka, when she was vacationing there with a friend. Her most recent work, Notes in the Wind, features a quaint yet quirky bookshop tucked away in a corner just behind the Beijing Film Academy.

Born in Malaysia, Jingliang’s childhood was filled with frequent commutes across the Causeway to school in Singapore. It was perhaps through this formative experience that she first stumbled upon the path of physical and psychological ‘displacement’. In one of her most well-received pieces of work, The Transplants (2013), she explores this very idea through her characters in a deeply personal andeven unsettlingly autobiographical way. Jingliang describes The Transplants as a “migrant’s story recounted in fragments”, and one that is “equally fragmented as the migrant’s own memory”.

During the New Waves session, Jingliang showed Open Sky, which was completed last year. Though it was shot entirely in Singapore, it features two characters who muse over the Great ‘Elsewhere; and the (clichéd) seductive dream of moving to New York City. The characters’ restlessness is palpable throughout the film. The shots are tightly framed, giving them a claustrophobic feel—perhaps mirroring the characters’ (especially the female’s) internal states. I loved the opening scene where the female character fiddles restlessly with the small bottles of condiments at a restaurant during its off-peak hours, stares into space, utterly disinterested in the food that she had ordered, and later fiddles with the decorative lanterns in the dining area. Everything about the scene displaces the character from her physical space, and gives off this ominous sense that she simply isn’t where she should be. She later contemplates the open night sky (and oh, the possibilities of life)—as she lies on the floor of a neighbourhood street soccer court with her male friend.

In essence, restlessness creates this state of ‘displacement’ in a person.

Before you dismiss ‘restlessness’ and the pandering of possibilities as a frivolous, whimsical and ephemeral pursuit, I would like to argue that at its core, the ‘displacement’ experienced by Jingliang’s characters (along with Adrianna and Jingliang herself) is curiously an earnest search for something more solid, rooted and concrete. You could label this ‘something’ as one’s ‘identity’ or ‘purpose in life’. I would also like to argue that though ‘home’ for Adrianna and Jingliang is a fluid space, it is also one that has clearly-defined characteristics.

The contours of Adrianna’s physical ‘home’ morphs as she moves from a foreign land to another. Yet you will realise through her sharing during the New Waves session, that she has the same earnest personal mission wherever she goes. In the same way we would normally describe ‘home’ as a space synonymous with comfort, residence and permanence, Adrianna finds her comfort, residence and permanence in her mission to improve the lives of underprivileged girls and women through her enterprising spirit and heart for these people, no matter where in the world they are.

Adrianna reminds me of a fulfilled (future) version of Jingliang’s sometimes indulgently wistful characters. Just like how Jingliang’s characters in Open Sky found comfort in sharing their existential anxieties in the wee hours of the night, Adrianna noted that “going home at 5am” during her youth “provided very interesting perspectives” on life. However, unlike Adrianna, many of Jingliang’s film characters are still very much in the early stages of finding a sense of ‘home’ in their displacement. Jingliang’s directorial style—one that bestows her cast members’ a large amount of freedom and flexibility— helps to express the insatiable restlessness of her films’ characters.

Jingliang is adamant that most of her short films are made as free from scripting and staging as possible. For example, dialogue in Open Sky was improvised on location by the actress Yam Yi Si, whom Jingliang shares was “at a similar crossroad in life, like her character”. In the last scene, Jingliang allowed the two cast members to “just talk and finish the film that way” to the point that “even the DOP (director of photography) did not know when to cut”. Sri Lanka Diaries was even less scripted, as it was spontaneously shot when she “suddenly decided” to point a camera at her friend while they were on holiday there. Notes In The Wind, her most recent film, is what she claims is her “least scripted” piece of work. When asked about how she came to adopt such a directorial style, she shares that one of her biggest takeaways from her experience at the Asian Film

Academy was that a director’s job sometimes is simply “not to impose”.

In a way, Jingliang has found her ‘home; in such a style of filmmaking. There is a certain rootedness and consistency in the way she chooses to tell her stories in such an unanchored manner. She finds her home in her near-obsessive archival of life’s fleeting conversations, quirks and idiosyncrasies. Through her films, she gives layers of meaning and heightens the significance of the casual and the ordinary. It was through her films that I started to see the tension between the unbearable lightness of restlessness (and accompanying flights of fantasy / ability to just up and leave)— and the similarly unbearable weight of the existential anxieties and gravities that often accompany such thoughts and dreams of the great ‘elsewhere’.

In the end, perhaps what Jingliang and Adrianna have shown me is that ‘displacement’ and ‘home’ may not be entirely contradictory concepts. One can feel displaced from the “home” or physical space (or country for that matter) that she was born in or lives in, and one can also find “home” in her physical displacement. One can be gripped by a rising restlessness and desire to explore possibilities, yet also use them to fuel a journey towards finding one’s concrete “something”, permanence and “home”.

Both Jingliang and Adrianna exhibit a remarkable ability to recognise and define what “displacement” and “home” are in their lives, and go a step further to reconcile these two concepts. For Jingliang, “displacement” is when she is mistakenly labelled as “non-Chinese” when she goes to China due to her tanned skin, but “home” when she is welcomed as a “local” by blends into the native communities of Thailand and Laos. “Displacement” is her fragmented memory of a Malaysian childhood, but one that has found a “home” in film—for film helps to investigate, reconcile and reconstruct. “Displacement” is lost characters, open skies, transplants and strangers, but “home” is found in travel narratives, video diaries and near-obsessive archival. For Adrianna, “displacement” is when creature comforts of a TV or sofa are few and far between during her stays abroad, but “home” is when she proudly makes a small space in a foreign worker dormitory in Indonesia her dwelling. “Displacement” is foreign lands, 5am nights, challenged conventions and less travelled paths, but “home” is found in social impact, educated Indian girls and newly-forged paths. Dedication, adaptability and an undying commitment to their respective crafts. “Home” has been by these two women, found.

You go, girls.