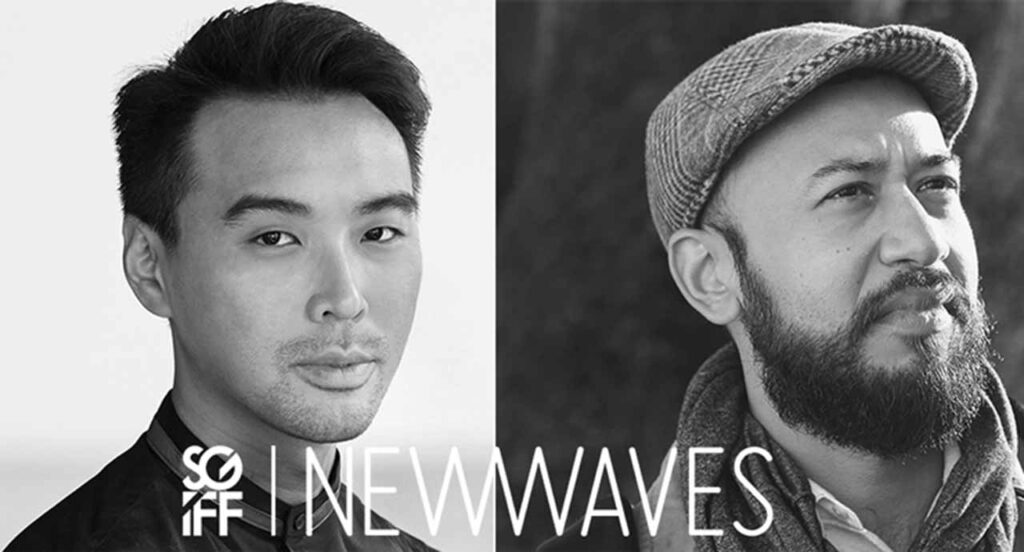

New Waves #2: Feminine/Masculine with He Shuming and Marc Nair

Two strangers – a Malay transgender sex worker and a Chinese beer girl – bond over cigarettes. A Hispanic housekeeper stands in a motel room, pondering what to do with a bag of money she just found. A Singaporean Chinese male, smiling happily, stuck on a tour bus filled with wannabe ajoommas.

These were some of the more persisting images that presented themselves in the second New Waves session, which saw filmmaker He Shuming and poet Marc Nair sit down for a two hour-long discussion over, among other things, two of Shuming’s films, And the Wind Falls (2014) and hoon/Ramlah (2008). Of the three images mentioned, only two are seen on screen – the last one being an actual scenario that Shuming would find himself in soon after the session.

Funny as it might sound, this may be a particularly important moment for Shuming, as it involves a journey for him to understand more about women who are at the same stage of life as his mother. He mentioned during the session that his mother was the inspiration behind many his films’ female characters, of which there are many.

And the Wind Falls, Shuming’s latest short which premiered at SGIFF in 2014, demonstrated his fascination with female characters clearly. It was screened at the start of the session, and features a motel housekeeper who finds two things in a motel room: a dead man, and a large bag of money. She tries to do many things with the money: hide it, use it to redeem her relationship with her daughter, and eventually return it. But the unearned money weighs down on her, threatening to resurface her ugly past.

Following the title of this session, a large part of the discussion for this film went into the idea of the absence of the masculine. The lack of fully-formed male characters – and the focus on female characters – has been a pattern in Shuming’s earlier works, such as Labour Day (2010) and Visiting (2008), and And the Wind Falls (2014) follows this trend. Male characters in the film take the form of passive, plot-filling characters, such as the man found dead in the room, and an oblivious sheriff, while the main conflict is surrounded by women: the housekeeper, her daughter and her caretaker, and a motel manager.

Shuming elaborated upon this absence. He finds a distance between himself and his male protagonists because of the ego involved; he finds it a lot more fun to create female protagonists.

“With female protagonists, it’s very hard to see them as one-dimensional,” he said. “With every good there’s always something – we’re not all good people – I mean, I could be harbouring dark thoughts. We all have that part of us within us, and I see that for my characters as well.”

Shuming added that he grew up in a very women-dominated environment – with his mother and two sisters – whereas men were seen in the background. As a result, he found himself using women as inspiration for him to understand his place as a filmmaker and a person.

Gender discussions aside, I liked that And the Wind Falls explores – intentionally or not – how greed can consume a person and bring out the worst in them. I believe that although the housekeeper’s intention in keeping the money was for good – to prove to her daughter that she can be an adequate parent – but the bag of money was ultimately just an easy way out of her problems. And the film showed that in taking the easy way out, more serious problems presented themselves at a later stage, such as when her daughter’s guardian called out her out (accurately) for giving them dirty money and accused her of relapsing into her old ways.

The orange motel used as the backdrop for the film took on a character of its own as well. It was inspired by the motel in Robert Altman’s 3 Women – another film that deals almost exclusively with women – and Shuming mentioned that he was interested in the motel as a temporary space that had “something very flat about it”.

It reminded me of a recent piece by the New Yorker, “The Voyeur’s Motel” that talked about a motel owner who created a special viewing platform in his attic to look at his guests in their most private moments, and as a result turning mentally unsound himself. And the Wind Falls has its voyeuristic moments too, where we witness the motel worker in the intense moments of her internal struggle; and in the way she constantly turns her head to check if anyone is looking at her. Additionally, I thought it was interesting how in a motel, passing guests could leave an imprint on other humans’ lives without any interaction happening between them.

Following And the Wind Falls, we saw an earlier short by Shuming, hoon/Ramlah. The style was immediately different: it was shot like a documentary, handheld and with long lenses, and barely had a narrative thread holding it together. hoon/Ramlah depicts a Chinese beer-lady and a Malay transgender sex worker working their late shifts, and later on in the night chancing upon each other and bonding over cigarettes.

“There’s a lot of beauty in the way a woman smokes. It’s not just alluring, there’s a certain sense of ownership of having (this) power. Usually you’re thinking – or (maybe) not”, Shuming mused.

A member of the audience mentioned that there was something voyeuristic about the way the women were shot: the camera did not follow the beer-lady into the toilet, and we only see her as she washes her hands in the shared basin outside, almost like we were one of the many uncles sitting around the coffee shop. This sense of being there with the characters added to the realism that the filmmaker wanted to convey, along with the genuine and at times awkward conversations between the two women.

For hoon/Ramlah, he wanted to allow two women in similar predicaments but with different backgrounds come together; to give them the freedom of saying whatever they wanted, be it about love, language, borders (between Singapore and Malaysia) or working class issues. It stemmed partially from his wish to identify with the Malay culture in Singapore, but in realising that it was absent explore it further as both a person and an artist in Singapore.

There were points where I could feel a real connection between the two women, especially towards the end of the film, such as when the sex worker tells the beer-lady, “You must learn Malay, you know?”. In freeing his actresses from the constraints of a script, he allowed them to truly empathise with each other beyond their acting roles.

Although the discussion then headed towards several directions, one being travelling (Marc talks about the importance of getting lost in an unfamiliar place, while Shuming feels that travel makes him realise how sheltered he is, and that he is still struggling to learn how to be an adult), all roads seemed to lead back home – to Shuming’s mother.

Throughout the session, he speaks of how he has a “healthy obsession” with his mother, and that many of his films seem to be inspired by her but at the same time was not directly related to her. Which brings us back to the third image in my head, that of Shuming being the only young man in a tour bus full of middle-aged ladies.

In the days following the New Waves session, he would be going on a guided tour (Marc’s bemused disapproval weighs heavy in the air) to Korea with a bunch of aunties. This would be part of Shuming’s ethnographic research for an upcoming feature film, Ajoomma, which may finally be about his mother, and also perhaps provide a continuing exploration on his understanding of the feminine/masculine in his work.