Structuring Comedy (II): Five Trees

In this two-part series, Joshua Ng examines how two shorts from the Southeast Asian Short Film Competition use comedy in two very different ways.

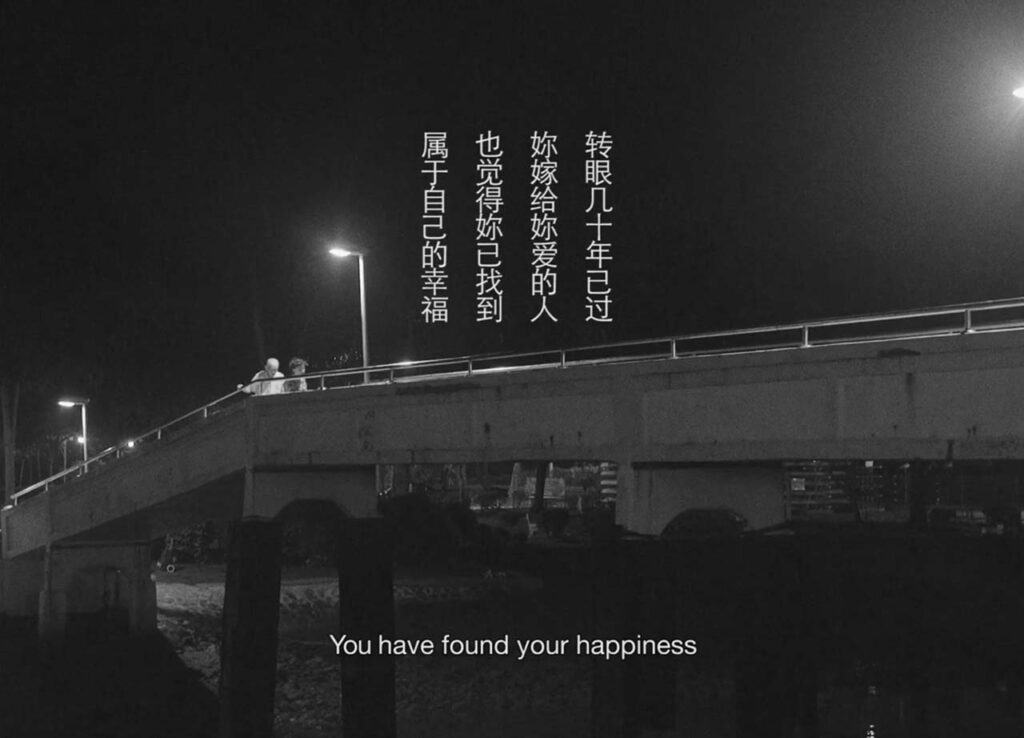

There is a juncture in 5 Trees precisely crafted to put a smile on our faces; a comedic interruption that punctuates the melodrama.

The film opens with central character, Mok confessing his feelings towards Keow in a letter. We are then casually informed that the latter’s response was eaten by a cat.

A cat.

It is an absolutely absurd twist that stands in stark contrast to Mok’s solipsistic ramblings. It instantly trivialises his tragedy.

The cat then contributes its thoughts on the matter. Director Nelson Yeo seems to be expressing his worldview via cat. Before I get to that, I want to bring your attention back to that moment first.

This anticlimactic juxtaposition between the sublime and the commonplace is known as ‘bathos’. The term was coined by Alexander Pope to describe unintentionally funny attempts at pathos or the act of appealing to the audience’s emotions. He observed that bathos obliterates any sublimity that came before.

In my opinion, what we have here is a case of intentional bathos (I hope).

Yeo uses it to forcibly effect a change in our perspective, prompting us to re-evaluate everything that built up to that bathetic moment. It’s like he’s saying, “hey, this sob story you invested your emotions in – it’s all just a joke.”

This dramatic perspective shift causes an emotional whiplash of sorts. It is as if Yeo first lures us into Mok’s myopic mind, then grabs us by the collar and pulls us out from this insular mind-set, forcing us to see the forest for the trees.

It is a simple but clever narrative trick that caught me completely off-guard, which is testament to Yeo’s prowess in selling us Mok’s maudlin story. Once Yeo tears down the false sublimity he built up in the first half, he presents an alternative perspective via the cat.

This cat is a cynic. It sees the characters longing for each other against the backdrop of eternity and having a mind of its own, it ultimately concludes that there is nothing special about this heartache.

“What has changed since these two poor souls left?”

“Nothing.”

“More fools are just walk the same paths and alleys,” it observes. Our heartbreak, our misfortune, our tragedies – they really aren’t all that unique.

Yeo’s usage of bathos leads me to believe that the cat speaks for him. Mok’s sob story was just bait, luring us to an awakening when we realise how pointless such regrets are.

I find it curious how this bathetic moment cleaves the film exactly in half, right down to the second. It’s undoubtedly a conscious choice by Yeo to devote equal screen time to both perspectives. Although it’s clear which perspective he tends towards, Yeo seems to acknowledge the validity of both.

Tragedy is just another Tuesday in the grand scheme of things but to someone in the thick of it, Tuesday can last forever. 5 Trees acknowledges this and encourages us to take a perspective on things.

The film’s title refers to a famously romantic spot under 5 Angsana trees near Clifford Pier in Singapore. Clifford Pier was also known as the Red Lamp Harbour, named for a red beacon that shone over the pier.

I asked my parents if they had ever gone there on a date. Of course, they had. Every couple did in the 80s. But that is not what my dad remembers the spot for.

He remembers the prostitutes. Streetwalkers solicited sailors right under the 5 trees, alongside dating couples.

Just goes to show that there’s always another perspective to things.

In part 1 of this series, Joshua analysed the use of comedy in Sorayos Prapapan’s Death of the Sound Man.