Of Labels and Truth

Taking themselves very seriously, two of this year’s youth jury members decided to interview each other on how this year’s SEA short films blur the lines between documentary and fiction.

On documentary and fiction as separate:

Tanvi (T): Among the films in this year’s SEA short films, there is only one film labelled as a ‘documentary’. What do you think is the point of this label?

Priscilla (P):I think the primary point of a documentary is to ‘show what is real’. Content-wise, when many think of a documentary, we think of it as fly-on-the-wall footage that show what is happening as it is. But thinking a bit more about it, isn’t there a limit to how real documentaries are? Not only do people behave differently when they know they’re being watched and filmed, the director could intentionally ask certain questions to only get certain answers, or even change the sequence of events to suit his storytelling intentions – to me, all these factors reduce the realness of a documentary.

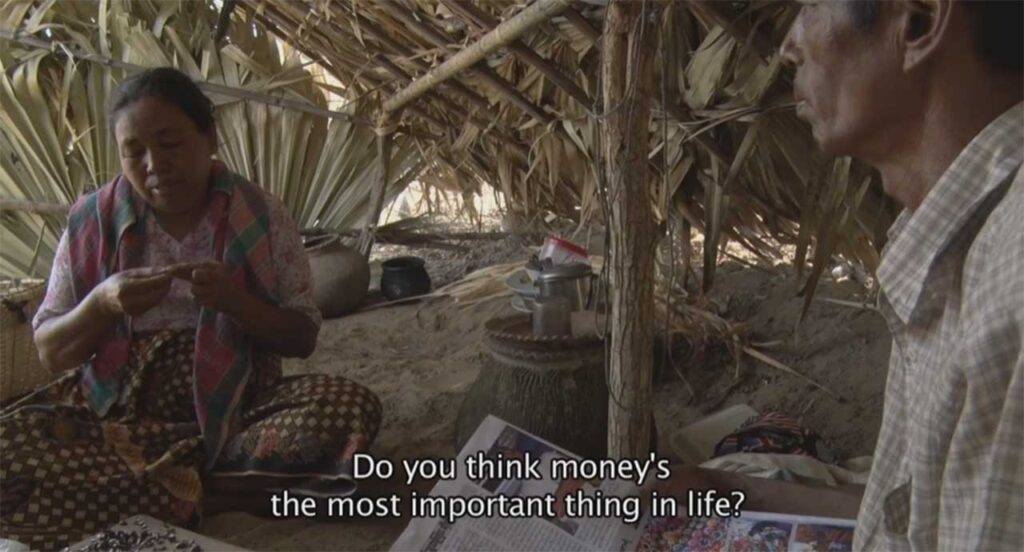

In Sugar and Spice – the only documentary among this year’s SEA short films – I think the effects of the camera and the crew can be clearly felt. At certain moments, the exchanges between the male and female characters feel almost scripted, with the intention of slowly revealing very specific issues – poverty, illiteracy, political problems and the tumultuous state of the nation. During these exchanges, what is real and unreal in their words and intentions begin to blur for me – is this how they would converse day-to-day to discuss their issues if they were not being watched? As soon as I find myself asking this question, the label of the ‘documentary’ is questioned.

That being said, I definitely think that watching documentaries could still be the closest to watching the real thing, but I think it’s necessary to take the label with a pinch of salt.

P: Which films in this year’s SEA short film selection challenge the idea of ‘fiction’ the strongest and why?

T: To an extent, I think all of them challenge the idea of fiction. If we go by the definition of fiction as something that is ‘made-up’, then all of the films undermine the idea that a made-up story does not point at issues and concerns that are very real.

Films like Arnie (by Rina Tsou) and Lost Wonders (by Loeloe Hendra) examine issues faced both by foreign migrants and by their families at home. In Lost Wonders, we see the pressure put on the older generation to take care of young children when their parents go overseas for better work prospects. The pressures on foreign workers themselves are clear in Arnie, especially in the scene where Arnie calls his mother and sister. He cannot even voice his problems because both of them are bursting with requests to send money home. In both films, the most harrowing thing is that death is a very casual and normal ‘occupational hazard’. So yes, even though these are ‘fiction’ films, it’s hard to say that the stories are entirely made-up.

On documentary and fiction as symbiotic:

T: What about you? Do you feel like Arnie had a realness to it? Or do you see it as a made-up story?

P: Arnie really demonstrates how the lines between a documentary and fiction blur into a film that fulfils both genres, so I actually still think of the film had a strong realness to it that could’ve been inspired by the story of Tsou’s uncle. The on-location scenes, the handheld shots and the non-actor cast really led me into thinking that the film was going to be a documentary about Filipino Seamen. During the credits, the dedication message clearly stated that the film was for Tsou’s uncle, whose name was Arnie. It’s these details that really endow Arnie with a “this actually happened” quality, and that feeling resurfaced repeatedly throughout the film.

I think that employing real stories and real places as starting points to develop films strongly encourages the viewer to rethink the different positions of different people involved within certain social, economic or political problems that audiences themselves may never experience. At the end of the film, when we find ourselves saying “Does this actually happen?” or “I can’t believe this happens”, then I think the director – by intentionally blurring the real and unreal – has made us feel something new, and has materialised a powerful statement into a hard-to-forget film.

P: Do you feel that this blurring of what is real and what isn’t is deliberate? Also, what affordances do the deliberate directing decision give the filmmaker?

T: Actually, I think instead of deliberate, it’s a natural outcome.

It’s a bit cheesy to say this, but the theme for the Singapore International Film Festival (SGIFF) this year is “Telling Our Stories” – and if you think about that especially in the context of Southeast Asia, then all of our stories are rife with social issues! Many of the films we have been seeing in the SEA short film programmes reflect the effects of poverty, corruption, genocide, or natural disasters.

So it’s not surprising to me that inevitably all of the films are grounded in some kind of reality, because I think a number of filmmakers living in this region are inherently influenced by its politics and therefore cannot escape addressing those issues even if they’re making ‘fictional’ films. Even a film as non-narrative and abstract as Demos, has political undertones because of the juxtaposition of caged animals with construction sites of housing complexes.

In terms of affordances – I would say that fiction offers the filmmaker a higher degree of freedom to tell their own truths, both formally and ideologically. They’re not bound by standard documentary convention such as on-location shooting, long takes, recording personal testimonials etc. Grandma Loleng is a film that comes to mind, because it is a personal story but entirely told in animation. The deliberate choice to use childlike sketches and bright colors amplifies the filmmaker’s interpretation of dementia and the trauma that incurred it because the film appears as though it’s told from the eyes of a child, but is laden with political undertones.

The juxtaposition of the colors with newspaper headlines referencing comfort women and the Japanese occupation of the Philippines is a jarring way to depict trauma because it combines a playful, almost naive aesthetic form with a very disturbing historical context. This impactful way of expressing repressed trauma might not be as easy to achieve if the filmmaker were to stick to standard documentary convention – especially not in a short film!

In a region where there is so much state-censorship, perhaps ‘fiction’ serves as a translucent blanket wrapped around very real social and political concerns.

On documentary and fiction as labels:

T & P: Has this conversation changed the way you think about how and why films are labelled?

T: Our conversation has definitely made me think about the different things that a label such as ‘documentary’ or ‘fiction’ can imply. I think that labels will continue to exist because they’re important tools in identifying and categorizing films. That being said, we need to learn to abandon any expectations we have of a film based on merely one word at the entrance of the cinema and instead focus on what we can take away from watching the film. It’s tough, for sure, but I think it’s entirely possible!

P: I agree – labels will continue to exist because they are important: they highlight the director’s intentions behind their work and indicate to a viewer what a film can be about. But at the same time, certain elements in Sugar and Spice show how the real and unreal can be blurred, while certain elements in Arnie can create a documentary-fiction co-existence within one piece of work, which goes to show that more and more, there is a fluidity towards what makes a fiction or a documentary, that filmmakers and film viewers should see. To me, this fluidity in film means that industrial and individual notions of labels need to be revised.

I guess this is where the Southeast Asian short film programmes come in. Within one programme, we have five films – that could mean five different interpretations of one film label. Since you have a ticket to a programme, wouldn’t it be a waste to focus on one or two short films? Rather than shying away from other works with certain labels (ahem, experimental?), I think when we choose to fully engage ourselves within the entire programme and see how certain labels play out, we’re not only making our ticket count, but also giving ourselves a challenge or a chance to taste something different. Who knows? Perhaps we’ll find an undiscovered appetite for something new.